Tri-city artists community characteristics include non-formalised activities and a reliance on the DIY method. Another important aspect is the support derived from social relations and the mutual flow of social capital, as well as the independent work of individuals who embrace a variety of tasks and projects, which often have an ephemeral character and exist within certain time frames.

The endless expanses of the Internet hold a meme that many representatives of the generation born in the 1970s and 1980s may find easy to identify with. “1990 was not ten years ago”, the inscription reads. We often seem to perceive the 1990s as only a decade away from the present day. However, we are in 2016 and the period that followed the democratic transition has largely become a matter of the past. It is not my intention to make anyone feel old, but rather to underscore that when searching for points of reference, we should turn our attention not to the final years of the 20th century, but to the first decade of the 21st century. What happened to that invisible decade, a gap in time that public discourse frequently appears to neglect?

My observations of the Tri-City and the local music scene leave me under the impression that the above-mentioned period does not exist at all in general awareness. As we discuss or write about the local phenomena in music, we all too often dive deep into the 1980s and 1990s as we pore over yass, Totart and the Gdańsk Alternative Scene, while the developments after the year 2000 seem to be shrouded in mist. Is it because not enough time has passed? Still, the first decade of the 21st century seems so much more interesting to me: the enthusiasm of the political and economic transformation had already faded, Poland became a NATO and EU member state, the music market entered a period of transformation, and the Tri-City music scene was gradually adapting to this new reality. Superseding press magazines devoted to culture, blogs and specialised music services gradually began to mushroom. [1] The major labels lost their vast influence as niche labels started to feature the most interesting content. It was also a time when the independent scene and the DIY movement needed to find themselves in a new situation – not necessarily as those who challenge the elites, but as those who follow an alternative and parallel route.

The group of visual artists who started to operate in 2002 under the banner “Friends from the Seaside” had strong ties to the music scene. Suffice it to say that there was a considerable overlap between both those spheres in Gdańsk, which has remained until the present day. It is difficult to indicate a single culminating moment in the Tri-City that began this overlap. Also, the music scene did not feature any considerable movement that would generate one consistent formation. New bands emerged gradually, groups of friends were formed, niche labels were established, which, in a more or less collective form, pioneered certain musical innovations and concentrated on research and developing their activity. Such grassroots activities beyond official institutions, on the margins, have become a characteristic feature of the Tri-City music scene.

It might be more of a coincidence than a relevant event, but the year 2002 saw the closing of Machina, a magazine that, since 1995, had played a similar role for popular culture in Poland as The Rolling Stone in America. Those who flicked through the pages of Machina with interest and listened to the CDs attached to the magazine remember the enthusiasm that accompanied the discoveries of new releases, artists and films. Today, the magazine enjoys a cult status and stands as a symbol of a certain transformation and the cultural permeation between East and West Europe. [2] Machina promoted culture in the Polish realm after the country’s transition to democracy, however, at some point time stopped working in the magazine’s favour. It was similar with the magazine Brum, which had breathed its last a few years earlier, in 1999. In turn, in 2003 a conflict with the publishers of the magazine Tylko Rock [Only Rock] led to a change of name to Teraz Rock [Rock Now]. The social and political situation was changing, as was the situation in culture. The above-mentioned turning points set the direction followed by the Polish music press, and therefore they reflect the situation of the entire music scene and its conditions. They might also be seen as breakthrough points when a top-down force had a galvanising effect on grassroots activities (in Gdańsk, such a seminal change was the closing of the Wyspa Gallery in Chlebnicka St.).

The Tri-City has always existed on the margin – even today no one ever comes here to carve out a career. People do that in the capital, which is the seat of major labels and media outlets, and it is easier to catch their attention. It is a factor that influences the way artists function on the Polish coast and shapes the position of music groups and publishing projects set up for longer or shorter periods. This context creates a relevant perspective to observe the subsequent initiatives that consolidated the Tri-City milieus. During the last fifteen years, those initiatives have significantly shaped the Tri-City music scene, which regularly brings together visual artists and musicians. Their essential characteristics include non-formalised activities and a reliance on the DIY method. Another important aspect is the support derived from social relations and the mutual flow of social capital, as well as the independent work of individuals who embrace a variety of tasks and projects, which often have an ephemeral character and exist within certain time frames. The Tri-City scene appears to believe that new ideas emerge frequently and they are worth putting into practice in different forms lest anything fades away.

Such non-formalised activities form a significant core of the Tri-City cultural sector, which receives the most modest funding on the one hand, while on the other it often provides public institutions with know-how and ideas for innovative projects. This can be seen in the examples included in this text – the described people and groups regularly collaborate with public institutions and NGOs. This is because, in spite of the lack of stability inherent in this form of activity, grassroots initiatives are proof of a very high degree of innovation and flexibility. [3]

The People are the Most Important

The first example of such activities came with the establishment of Pracownia Ludzie Gdańsk [Studio People Gdańsk] in 1996 by Michał Skrok (aka Bunio), Piotr Szwabe and Krzysztof Topolski (aka Arszyn). The Studio was a harbinger of the group Ludzie [People], which was set up later, and was a space that anticipated a regular exchange between artists active in the fields of music and visual arts.

In spite of the fact that the collective was formed several years prior to 2002 – the seminal turning point of this text – it is worth mentioning in order to highlight two people who later formed part of the local scene in a variety of configurations.

Bunio and Arszyn – the musical side of the collective – had already been involved in making music. At the beginning of the first decade of the new millennium, Bunio recorded two very good albums released by the label Teeto Records: Perz (2001) and Historie + R (2002).[4] They emanated a climate of experimental electronic music and abstract hip hop familiar from the releases of the label Anticon and its star Clouddead. Deeply embedded in electronic music and experimentation, Skrok’s music gravitated towards productions of To Rococo Rot. That tendency became manifest in the album Palembuho by Legwan Allstars – another of his projects – as well as on the last solo record Lo-fi Symphony, where Bunio gave proof of the development of his skills as a producer. [5]

Arszyn was active in the bands Kobiety and Dzieci Kapitana Klossa. In 2001, the artist released a first solo CD, entitled Arszyn, followed a year later by Z werszków pierwszy, released by the label Nefryt Records. Insofar as the first album preserved Arszyn’s fascination with experimental post-rock, the second record gravitated towards post-industrial music, electroacoustic music, Musique concrète, noise and ambient, defining the direction of the artist’s further investigations.

The year 2004 saw the release of his album Unitas Multiplex by TNS Records RXS. It comprised material recorded between 2000 and 2004: sounds constructed using piezoelectric converters, acoustic noise generated by condenser microphones, field recordings, acoustic percussion instruments and a variety of samples. The record featured Tomek Szwelnik, who improvised on the piano, as well as Bunio from Bass Station. However, a project that seems to be of seminal importance is Ludzie, which the two artists developed as a parallel avenue of their activity. It is a perfect example of a platform of meetings and musical activities created using one’s own resources. Initially, the band operated as a duo and was characterised by abstract lyrics, broken and volatile tempo, as well as punk-rock energy. Soon, the two musicians were joined by the trumpeter Tomasz Ziętek, while the music of the group became more delicate and acquired a more avant-garde appeal. During that period, Ludzie recorded more than twenty compositions. Later, the music and make-up of the band underwent ongoing transformations. Under the name Ludzie Aviomarin, the band merged jazz with punk; under the name Ludzie 02, they returned to the expressive formula characteristic of the initial period of their activity; as Szklaneczki, they penetrated dance music culture and eventually they found a home in the atmosphere of electroacoustic (post-rock?) sound collages. [6]

Their ideas eventually materialised in the album Sopot Surround, released in 2003 by the label Post_post. Besides Bunio, Arszyn and Tomek Ziętek, other musicians who contributed to the recording included: guitarist Mateusz Kuderski and bassist Wojtek Mazolewski. In his review of the album, Rafał Księżyk highlighted the conglomerate of featured musical means and styles, a mix that continues to characterise the Gdańsk scene:

The abstract instrumental themes merge post-rock, jazz, abstract hip hop, ambient and electro. A massive groove acts as a unifying force but the appeal is determined by an unpretentious search for tones and climates – totally above divisions, without attachment to specific styles, as well as a certain garage roughness, which, alongside the soothing atmosphere and the poetics of new sounds, sets the unique tone of the record. [7]

Sopot Surround was one of the most significant records on the Tri-City scene released during the first decade of the 21st century and, sadly enough, it also marked the end of the band’s activity. In a modified make-up, the musicians – without Topolski – released a double album two years later under the name Peepol (including a live recording from the Porgy & Bess club in Vienna). The band reactivated to perform on several occasions in 2007, and the musicians published three pieces on their Bandcamp profile in 2015 [8] – again as a duo. However, for the time being, a real and long-term reactivation is highly unlikely.

Musical Colonies on the Fringes of the City

Another place that left a significant imprint on the musical scene of the Tri-City were the premises of the former Gdańsk Shipyard and the Kolonia Artystów [Artists’ Colony], which was established there in 2002. The shipyard was detached from the rest of the city – occupied and inaccessible – and therefore, upon the initiative of Roman Sebastyański, the company Synergia 99, which purchased part of the premises in 1999, decided to invite artists to the area. It took just one year for two former shipyard buildings to start brimming with life – the old Telephone Exchange and the Director’s Villa, in which the Znak Theatre found its seat. What is more, the Model Workshop and the so-called Barracks began to develop – single-storey buildings near the Occupational Safety and Health Hall, where local musicians opened their rehearsal rooms and recording studios. Even though the Colony occupied a specific territory, it functioned rather as a label that referred to a certain group of artists active beyond the system of public institutions on an independent and entirely grassroots basis. It was an informal movement and the artists involved perceived themselves as individuals acting autonomously – as atoms, and not as a solid community that could unite or become associated for the sake of achieving a specific goal. In fact, such an approach turned out to be missing when the new owner of the Colony’s site – Baltic Property Trust from Denmark – forced the artists to leave the shipyard premises in 2007. [9]

The Colony was established by a group of people active in the field of contemporary art. The majority of them were students and graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts on the lookout for studio spaces. The Colony offered a combination of social, professional and quasi-family life – a “lifestyle community” was emerging. Its significant aspects included self-oriented activity, mutual inspiration and joint experiments – many projects were conceived and materialised simply because the artists were living close to each other. It was a space to work in at night, when it was possible to organise loud concerts. The residents were at the same time the artists, the audience, the partners and the critics, who stirred up a creative ferment in that area. A community spirit was being forged that was in contrast to the other artistic entities on the shipyard premises, which were more formalised, and to the employees of the Gdańsk Shipyard – people from outside the shipyard, from beyond. For the workers, that industrial space was a workplace, but for the artists it blurred the border between working space and home. [10] In an informal way, the Colony (given its structure or rather lack of it) stood in opposition to the Wyspa Institute of Art – a formalised non-governmental organisation.

One of the first residents of the Artists’ Colony was Krystian Wołowski, who introduced one of his first musical projects as early as 2002. The band Uniform was established alongside Adam Hryniewicki, Mateusz Kuderski and Norbert Walczak. Rather than a regular band, it was supposed to become an ephemeral collective of artists representing various disciplines, which would undergo constant personal change. Another of his bands was Trismegistos – both those groups included musicians who later formed the group Dick4Dick, established soon afterwards. [11]

Drink my Kefir

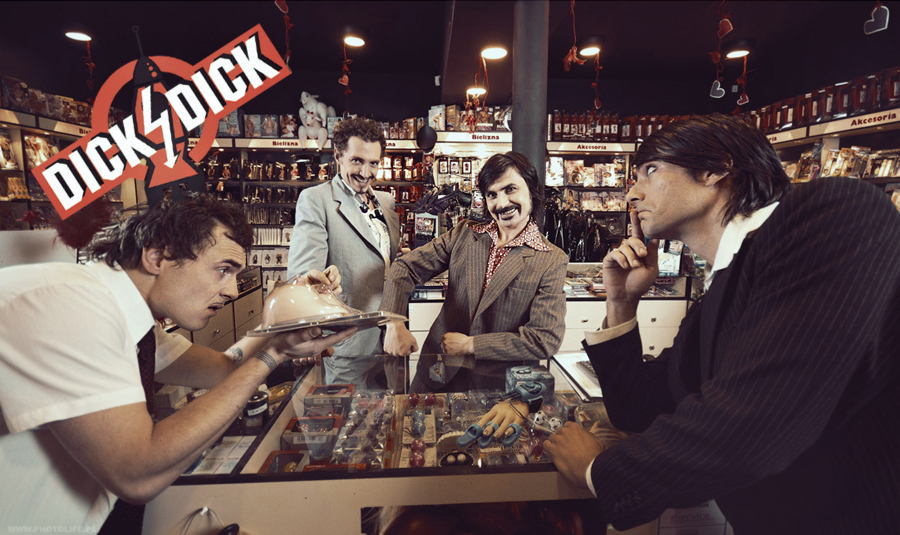

Few other groups in the first decade of the 21st century gave proof of such a strong symbiotic relation between music and visual arts. Dick4Dick was formed somewhat for kicks (and became typecast as such for many years to follow), but at the same time it engaged in an intelligent mockery of popular culture by deploying irony, wittily engaging their listeners and opening up to a play on different conventions. One of the most recognised Tri-City bands (whether you liked them or not), it was at the same time one of the most characteristic groups on the Polish scene. The musicians were unrivalled in terms of the pace at which they conceived their stage image.

The establishment of the group came as a result of an encounter between four artists: Krystian Wołowski and Adam Hryniewicki, who resided in the Artists’ Colony, Michał Bunio Skrok known from Studio People Gdańsk, as well as Maciek Szupica, a visual artist who significantly enhanced the visual side of the band. The latter was in charge of visualisations during performances, as well as stage outfits and music videos recorded in a variety of different forms. Szupica created visual works for artists such as Gaba Kulka, Paweł Kukiz and DJ Vadim. He was awarded several times at the Polish music video festival Yach Film, including the Grand Prix for the video Dziwny jest ten kraj for the band Pink Freud.

The musicians came up with nicknames – Nygga Dick, Dick Dexter, Bobby Dick and Wet Dick Jr, and later, with changes in the make-up, the new members also received new monikers.

The four artists took delight in mocking the conventions of rock and metal music, but at the same time they composed catchy rock’n’roll and electronic hits – Drink My Kefir and Technology still enjoy the status of classics now. The artists concentrated heavily on their image, and turned their performances into genuine shows – they changed their outfits, poured kefir over themselves, created mocking and debauched photo sessions, performed half-naked wearing make-up or with colourful visualisations in the background.

They navigated the waters of kitsch while playing electronic music in a powerful live rendition. They transformed well-known hits into songs with sexual undertones, borrowing from David Bowie; they performed in space suits or wearing Kiss-style makeup. They played juicy electro that adorated love, pornography and desire. The group sounded akin to Bon Jovi, Depeche Mode and The Human League, and they combined the old and the new. The already mentioned hit Technology was a reference to Queen’s Radio Gaga, while Drink My Kefir – referenced Black Sabbath’s Paranoid. In a single piece, the band combined their fascination with Hot Chip, LCD Soundsystem and Sabrina. It was not just a matter of girls shouting under the stage – Dick4Dick was the first Polish band with a consistent concept that embraced both the sound and the image. The musicians themselves admitted that their goal consisted of creating their own musical-visual language characterised by change and development.

Shit will Always Rise to the Top

The Academy of Fine Arts was and still is a major reference point for the music scene of the Tri-City. Although it is a public and state-owned institution, the students and teachers have included individuals engaged in grassroots initiatives and members of artistic groups.

An example of such an initiative was the establishment of the group Krecha (comprising Maciek Salamon, Maciek Chodziński and Michał and Marcin Sosiński). They published their own zine, which was visually attractive and became noticed outside the artistic circles due to an action involving flour in an envelope in which one of the issues of the magazine was released, an action that was misunderstood by the directors of CCA Łaźnia. [12] Yet, insofar as that activity was strictly visual, it was the establishment of the band Gówno, [13] with the already mentioned Salamon on vocals, that marked a transfer to the field of music. The members of the band wrote about their work in a way that is characteristic of the majority of the projects described in this text:

There is a connection between the visual arts and the sounds that GÓWNO releases. Understanding the band’s work only in the categories of sound does not fully reflect the nature of GÓWNO. If we gather the work of individual members of GÓWNO, it turns out that GÓWNO is active in the field of painting, graphic design, visualisations, performance, installations, art zines, radio projects and sound installations.[14]

The band was formed in the summer of 2009, initially as a trio – as well as Maciek Salamon, the musicians included Tomek Pawluczuk on drums and Piotr Kaliński on guitar. Encouraged by Maciek Szupica, visual artist and musician Adam Witkowski also joined the band.[15] In 2003, under the label Pracownia Ludzie Gdańsk, Witkowski released his first album 0404, while one year before he had been active as one of the creators of the first Friends from the Seaside exhibition. Witkowski also participated in projects such as Radio Copernicus and Lektury Obowiązkowe, he formed the group Samorządowcy with his daughter Maja, and he initially formed the duo Tatrzańska 88 with Maciek Salamon, and currently the group Nagrobki. Currently, Witkowski is active with Mikołaj Trzaska in the band Langfurtka. We should also mention his solo releases as Andrzej Baphomet and the duos with Piotr Rubiecki (Radio Kaliash) and with Michał Miegoń, as well as the establishment of the ephemeral label Masz z 60 kopii Records, with which he published several albums in just 60 copies. [16]

When Kaliński left for Great Britain, the band was joined by the bassist Marcin Bober, also a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts who was heavily engaged in various musical projects. In 2006 and 2007, he co-created the duo Efektvol with Tomasz Klimkiewicz – a duo whose style and sound bore reference to the electronic music of the 1980s. Between 2004 and 2010, Bober played solo as Loyal Plastic Robot, whose two records were published by the Polish label Elektropunkz, and one single was even released in Columbia. Bober also contributed soundtracks to animated films created by the visual and street artist Mariusz Waras (who also formed the audiovisual project Fabryka with Topolski). [17] The other members of Gówno have also been active in different projects: Kaliński works under the nickname Hatti Vatti, Pawluczuk is still a member of the band Trupa Trupa. The first impromptu performance at the PiTiPa gallery prompted the artists to continue their musical activity.

After the first rehearsal (with extra musicians) we recorded an album, after the third rehearsal we played a gig, and after the gig we sold all copies of our first record. At the beginning, we wanted to start a punk band in which we certainly wouldn’t pretend we could play musical instruments. We’ve never seen ourselves as outstanding instrumentalists. [18]

October 2009 saw the release of the album To nie jest kurwa Pink Floyd, which reflected the character and roughness of the band’s music (with the underpinning ideology already signalised in the title: This Ain’t No Fuckin’ Pink Floyd). As a quintet, the band played concerts and performed at festivals. Three years later, they recorded the album Czarne Rodeo, which was released as a CD with an extended graphic layer, and the band proclaimed a music genre called rodeo-punk. [19] The musicians created everything single-handedly – from the visual side of their performances, to their album covers, to their music videos. Half of the band members still work in a similar way: Maciek Salamon and Adam Witkowski, who have so far released two albums as Nagrobki. In one of the interviews, the musicians compare their method to punk, but underscore its different origins – the Academy of Fine Arts: “We gained our DIY experience from fine arts. We learnt that at the Academy of Fine Arts, not at a squat.” [20]

Another person affiliated with Dick4Dick is the current lecturer and graphic designer of the Academy of Fine Arts, Adam Kamiński, who recorded two albums as Paralaksa alongside Wojtek Mazolewski (v. 2.0, a re-edition of the first album released by Pracownia Ludzie Gdańsk and the concert album Live – the former in 2002, the latter in 2006).

Pursuing his musical fascinations outside Dick4Dick, Maciek Szupica formed the audiovisual “Gypsy” project Gypsy Pill[21] (with Salamon, Hryniewicki and Tomek Wierzchowski), called a party-hooligan collective (the musicians also adopted Gypsy nicknames: Don Toni, Gee Gee, Little Vania and Mucho). That initiative grew out of the audiovisual project Cavalleris. [22] Szupica’s activities culminated with The Saintbox, co-created with Gaba Kulka and Olo Walicki [23] – a project that combines sound and image – and with the production of the music video Tęcza Rainbow for Dorota Masłowska (as well as supporting vocals in the song).[24]

The visual arts circles regularly mingled with the musical circles, and therefore when Warsaw organised the festival The Artists [25] in Gdańsk for the first time, with the idea of presenting sound and music projects by visual artists, such liaisons had already been de rigueur for a long time.

It’s a Gdańsk Melody

In 2015, an album was released by the band Wolność. Comprising Wojtek Juchniewicz, Adam Witkowski and Krzysztof Topolski, the group’s activity came as the most distinctive effect of the project To Nie Ta Melodia, organised in 2013 by the New Artists’ Colony.[26] This time, it was not a matter of a specific group of artists working towards a certain goal, but rather a meeting, a grassroots initiative organised without any financial support whatsoever other than the funds of those involved. Musicians were invited to participate – artists who represented alternative rock and electronic music rather than improvisation – and to draw lots to arrange the configurations on stage; thus, they became completely detached from their own bands. The goal of that procedure was to generate combinations that could probably never happen anywhere else because the musicians – often hailing from different environments – would not have had a chance to meet. This peculiar series of encounters was far removed from a typical jam session: “Rejecting the routine is the very method that the organisers of the entire undertaking want to achieve; it’s one of its goals – to broaden the experience and integrate the alternative scene of the Tri-City.”[27]

Wolność turned out to be the most distinctive effect of that encounter – the band has been performing on stage until the present day, and has also released a record featuring Olgierd Dokalski and Michał Bunio Skrok.

To Nie Ta Melodia is yet another and also the most topical example of a grassroots and fully independent Tri-City initiative that was formed spontaneously and on an entirely volunteer basis. An important aspect of the project was the fact that it relied to a minimal degree – compared to the previous examples – on connections between friends and acquaintances as the initiative involved individuals from beyond people’s immediate circles. The random aspects and the encounter in a single spot made it possible to launch collaborations between people from the entire Tri-City area – people who would otherwise be unlikely to meet at the studio (another “fruit” was an album recorded together by Witkowski and Michał Miegoń). The activity of the Colony also provides an example of a bottom-up process that shapes culture, even though the entity functions as an NGO in terms of its structure. Sylwester Gałuszka currently also organises the Open Source Art Festival, and in 2015 he reactivated Strajk (previously active in 2007 and 2008), as well as the cycle of concerts 3w1 and other musical and visual events. Since 2015, the new seat of the Artists’ Colony has been located in a building in Grunwaldzka St. under the New Colony banner (previously located in Miszewskiego St.)

Mutual permeation between visual arts and music can hardly be avoided given the necessity of creating a stage image, album covers, music videos and the entire atmosphere surrounding the band. As the musicians of the band Nagrobki mentioned in an interview for the magazine Popupmusic.pl, [28] many famous musicians graduated from art schools: Kim Gordon, John Lennon, Graham Coxon, Eric Clapton, Jim Page, Keith Richards, among other figures – great examples of the universal character of this phenomenon worldwide. For many people, such liaisons came as no surprise, but with regard to the Tri-City scene, that mix of two worlds stirred up a considerable ferment and led to a cumulation of ideas, the establishment of new bands, album recordings and concerts. Thus, our local scene grew significantly during the first dozen or so years of the 21st century, and its legacy has created a landmark on the Polish independent scene. The significance of the performative element, present in the activity of both visual artists and musicians, is underscored by Adam Witkowski, who points out that performance – a term seemingly reserved for the domain of the visual arts – is also present in the work of musicians:

In English, the meaning of “to perform” does not refer to performers, which means artists active in the field of performance art. Whether you play in a hard rock band at a motorcycle festival or only a single sound as Napalm of Death at the festival The Artists – it is always a performance, a kind of slightly theatrical form of expression. [29]

I hope the readers will agree that

Witkowski’s statement seems to effectively encapsulate the musical activity

around Friends from the Seaside.

[1] Such websites include: popupmusic.pl (previously popupmagazine.pl), porcys.com, screenagers.pl – to offer just a few examples.

[2] Machina was reactivated in 2006 in a new form, and in 2011 it became an online magazine, but it closed down after a while. More: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Machina_(czasopismo) [access: 1st of April 2015; all further online addresses were checked on the same date].

[3] Sławomir Czarnecki et al., Poszerzenie pola kultury: diagnoza potencjału sektora kultury w Gdańsku (Gdańsk: Instytut Kultury Miejskiej, 2012), pp. 49-51.

[4] More information about the two records is available at the blog czyni.tumblr.com: http://czyni.tumblr.com/post/83804006676/teeto-i-postpost

[5] Review of the album Palembuho by Legwan Allstars; http://neurobot.art.pl/03/review/legwan.html

[6] The work of M..Bunio.S is described at: http://rozrywka.trojmiasto.pl/M-Bunio-S-a15.html

[7] R. Księżyk, Ludzie “Sopot Surround”, Paralaksa “V 2.0”, Antena Krzyku 2003, no. 2; also available at: http://seeyousoon.pl/produkt/sopot_surround,ludzie,8650

[8] https://arszyn.bandcamp.com/album/wielka-czarna-muzyka

[9] R. Sebastyański interviewed by Jolanta Woszczenko [in:] Kolonia Artystów w Stoczni Gdańskiej 2001-2011, ed. Jolanta Woszczenko, (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Niezależne, 2011).

[10] A. Koźlik, Kolonia artystów – paradoksy [in:] Kolonia Artystów w Stoczni Gdańskiej 2001-2011, ed. Jolanta Woszczenko, (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Niezależne, 2011).

[11] Kolonia Artystów w Stoczni Gdańskiej 2001-2011, ed. Jolanta Woszczenko, (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Niezależne, 2011).

[12] Incomplete documentation of the activity of the group Krecha is available at the group’s blog: http://krechamagazine.blogspot.com/

[13] The name of the band in English is “Shit”, hence the reference in the subtitle – translator’s note.

[14] https://www.facebook.com/Zespół-Gówno-314703726119/info

[15] Gówno. Wywiad z Adamem Witkowskim i Maćkiem Salamonem [Adam Witkowski and Maciek Salamon interwieved by Jakub Knera], Popupmusic.pl, http://www.popupmusic.pl/no/36/artykuly/449/gowno-wywiad-z-adamem-witkowskim-i-mackiem-salamonem

[16] J. Knera, Krzyżacy czytają “Dziady” na Halloween, Trojmiasto.pl, http://rozrywka.trojmiasto.pl/Krzyzacy-czytaja-Dziady-na-Halloween-n42655.html

[17] A note on Marcin Bober’s musical work: http://www.marcinbober.pl/index.php?id=portfolio_dzial&dzial=Dźwięk

[18] Interview with the band Gówno: http://muzyka.dlastudenta.pl/artykul/Gowno,48094.html.

[19] Gówno…, op. cit.

[20] Z zespołem Nagrobki rozmawia Jakub Knera, Popupmusic.pl, http://www.popupmusic.pl/no/48/artykuly/610/nagrobki–wywiad

[21] A note on the band Gypsy Pill: http://muzyka.onet.pl/gypsy-pill-oni-podbijaja-scene-klubowa/k55gr

[22] Music video of the group Cavalleris: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nw5IN7Oox94

[23] The Saintbox. Olo Walicki, Gaba Kulka, Maciek Szupica – wywiad [interview by Jakub Knera], http://www.popupmusic.pl/no/29/artykuly/343/the-saintbox-olo-walicki%2C-gaba-kulka%2C-maciek-szupica—wywiad

[24] Mister D. feat Monsieur Z. “Tęcza”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V9XOtdXY9kQ

[25] A note on the festival The Artists: http://www.zacheta.art.pl/pl/the-artists/the-artists-2013

[26]I use this name in order to differentiate between the activities of Fundacja Kolonia Artystów seated in Gdańsk’s Lower City and Wrzeszcz and the activities on the premises of the shipyard, which came to an end in 2007.

[27] Description of the project To Nie Ta Melodia: http://www.kolonia-artystow.pl/article/to-nie-ta-melodia/184

[28] M. Salamon, A. Witkowski, Z zespołem Nagrobki…, op. cit.

[29] Cyt. za M. Salamon, A. Witkowski, Z zespołem Nagrobki…