Marion Cousin and Kaumwald move Iberian songs from the collective regional memory into a broader context, as if wanting to engage listeners in a peculiar game. This is contemporary narrative, where the lyrical layer is used as a vehicle to communicate content that is much less pleasant.

Translation: Aleksandra Szkudłapska

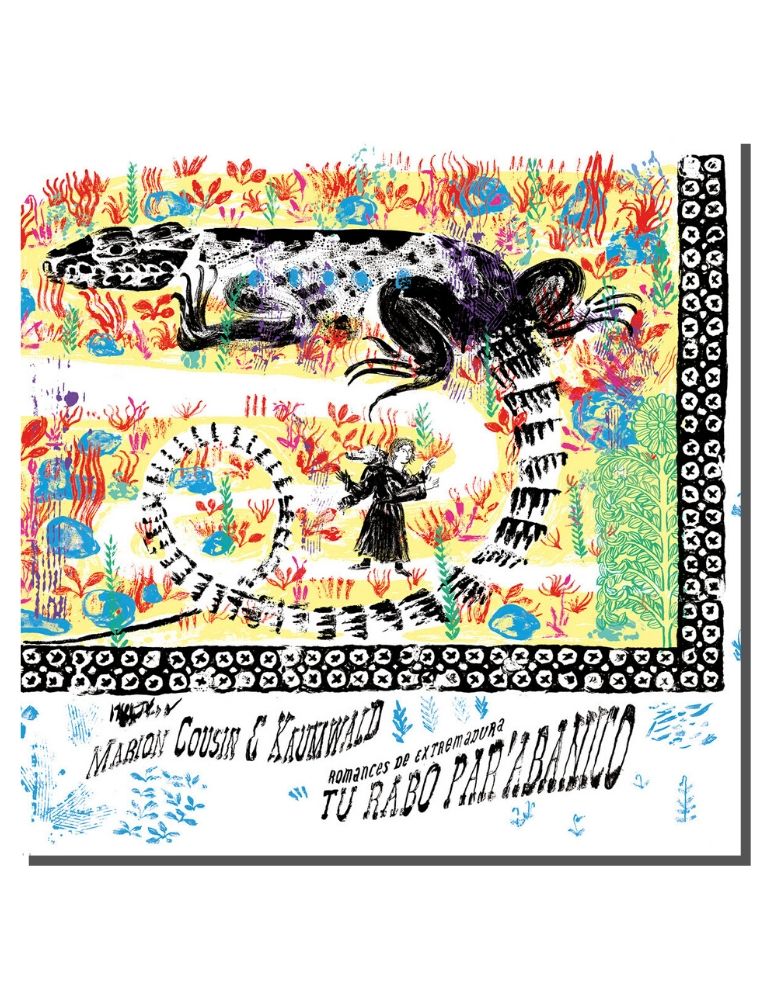

The appeal of traditional music in a contemporary setting has already appeared in my review of Tremor festival, where an orchestra enraptured the whole town, which joined in the singing of melodies from the Azores. Even I, a stranger unfamiliar with the context, felt great surrounded by this regional heritage. The same thing happened with Tu Rabo Par’abanico – an album released by singer Marion Cousin and instrumental duo Kaumwald. This music is informed by traditional songs from the Iberian Peninsula, yet the melodious, song-like forms evolve into prayer, mantric litanies surrounded by an intriguing collage of electronic sounds, noise and sampledelia. The text layer, however, is often downright terrifying – and topical even today.

Kaumwald stands for Ernest Bergez and Clément Vercelletto, 2/3 of the über-interesting ensemble Orgue Agnès, whereas Cousin has previously played with June et Jim, and in 2016, together with Gaspar Claus, she released Jo Estava Que M’Abrasava, where she revised work songs and romances from the Spanish islands of Majorca and Minorca. On that album, she was accompanied by just a cello, but now the music is more colourful and mysterious. In turn, in 2018 Bergez presented an electronic rendition of French folk from Occitania on L’Espròva released under the moniker Sourdure.

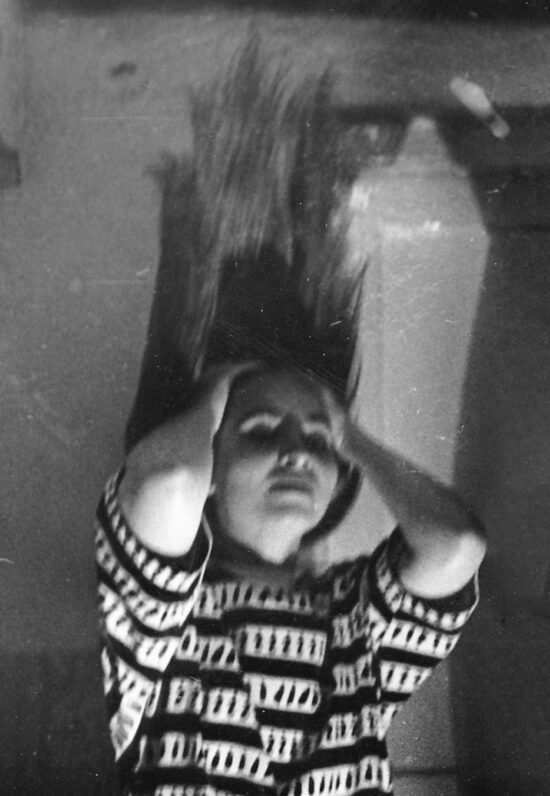

Cousin sings lyrical, fairy tale-like songs, but do not be beguiled by her sweet voice. It’s not that simple to get to know the content of the lyrics, sung in Spanish and Old Spanish, with French translations provided in the booklet. The timbre of Cousin’s voice is absolutely beautiful, and she brilliantly delivers line after line, with emphasis that may be hard to interpret, but the way she does it is pure magic, even if it may sometimes be near-impossible to decipher for foreign listeners. Trying to keep up with the words she sings, which often melodically blend into one, resembles moving around a mystical linguistic labyrinth. Subsequent lines sound like spells, and legends in her interpretation take on a new depth and dimension. Yet these lyrics, which at first seem to recount Iberian folk tales about wolves, a princess waiting for her lover in a castle or a girl locked in a tower, often convey dramatic stories that – unfortunately – sound very topical today: stories of women who, trapped in toxic relationships and abused in a patriarchal society, do not cease to dream. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

This contemporary edge is largely due to Kaumwald, whose music, rather than being based on simple chord progressions and song-like structures, is open-ended and has a near-improvised character. Despite its clear structure, internal pulse and beat, which suspends Cousin’s syllables and words, this sonic tissue is dense and diverse. Raw sounds, samples, cracks, electronic clicks and ever-denser patches of noise follow a controlled harmony, but there is also an abundance of fragments that are much easier to read, such as the quasi-orchestral ending of “La bastarda y el segador” about female desires or the ethnic, drum-based “Griselda” with its sonic sampledelia in the background, which tells the story of a seduced girl. At times, Cousin’s voice is in the foreground, overshadowing the rest, only to hide behind the resonating sound a moment later. It’s either clear and lyrical, or entwined in a net of vocal manipulations that only deepen the fairy tale-like, yet thoroughly modern mode of expression, even when she’s using autotune in “Gerineldo Fils”. The quintessence of this peculiar lyricism is the longest track on the album, “Delgadina”, with elements of musique concrète in the intro that soon morphs into bubbling beats, with Cousin’s voice oscillating between singing and spoken word. This diversification of vocal techniques and music reflects the text layer – what may at first sound like lullabies are in fact stories filled with distressing sexual relations, enslaved women or incestuous relationships.

Tu Rabo Par’abanico seduces and entrances with its balance between evocative ballads and electrified music.This dualism perfectly conveys the disconcerting undercurrent of these seemingly charming songs – even the word “rabo” in the title means both a tail and the male sex. Does the rhythmical repetitiveness of these appealing Iberian chants – where Cousin charms us with her voice, unique articulation and prolonging words to the accompaniment of intriguing sonic layers – hide a terrifying underside about patriarchal reality? I am immediately transported to Michael Haneke’s White Ribbon, where evil was lurking behind an image of a seemingly tranquil rural community. Cousin+Kaumwald move Iberian songs from the collective regional memory into a broader context, as if wanting to engage listeners in a peculiar game. You really have to go deep into this record to hear the contemporary narrative, where the lyrical layer is used as a vehicle to communicate content that is much less pleasant.

Marion Cousin & Kaumwald, Tu rabo par’abanico, Les Disques du Festival Permanent