Rastilho is a personal comment on the contemporary world, the simplest possible gesture: reaching for an instrument, playing, and looking towards the samba tradition to make a statement about Brazil under Bolsonaro’s rule.

Translation: Aleksandra Szkudłapska

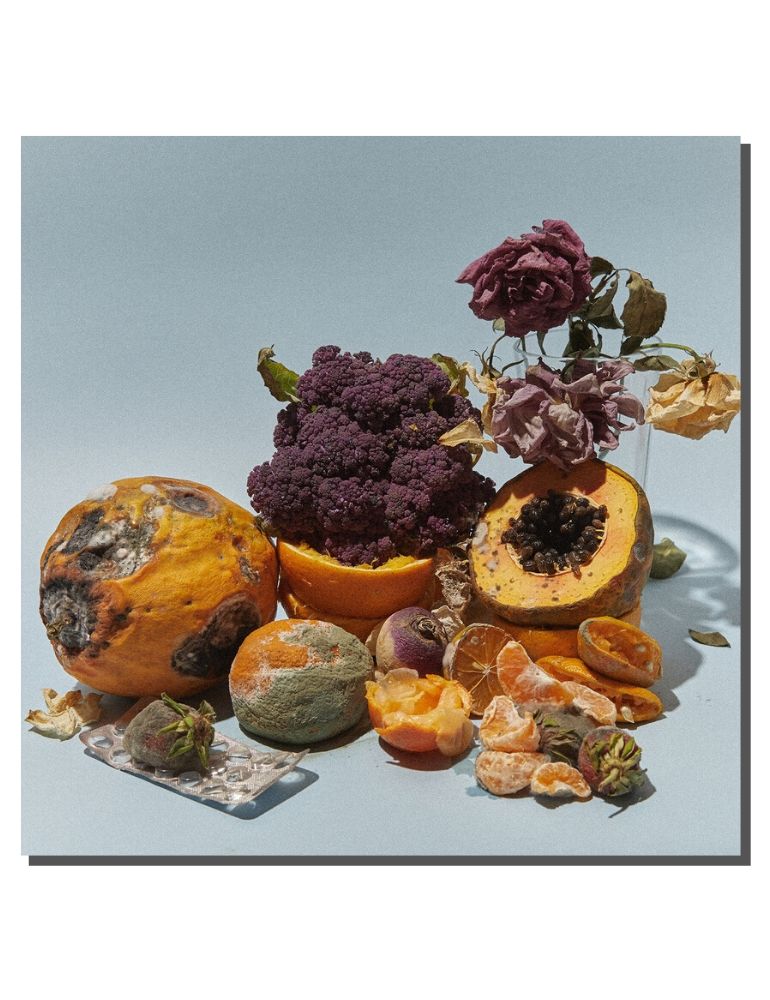

At first glance, the cover of this record looks like a Renaissance painting: densely arranged fruit, leaves, vivid citrus colours. Look closer, though, and you’ll see that most of them are in fact rotten. Pablo Saborido’s photograph used as visual representation of Rastilho shows decay.

The record was made by Kiko Dinucci, whose CV is rather packed – I first heard him on Metá Metá’s albumMetaL MetaL, which explored Afro-Brazilian traditions. He also played samba in Bando Afromarrônico, created polyphonic deconstructions with Passo Torto, and two years ago made an appearance on Elza Soares’ Deus é Mulher. His roots are in guitar music: on the one hand, he looks towards the Brazilian samba tradition played by Baden Powell, Gilberto Gil, João Gilberto or Jorge Ben, but he is also no stranger to electric guitar, having explored metal and punk, and co-founded Personal Choice in the 1990s.

Rastilho is a return to both. While the music has a warm, samba-like sound, it is characterized by compulsive, impetuous strumming, like in punk; the instrument sometimes sounds like percussion. Dinucci plays in a raw way, spitting out sounds devoid of any effects, which reminds me of Tom Carter’s Long Time Underground. Not in terms of aesthetics, of course, but in terms of using the guitar to spin a narrative about reality, use its healing potential. Dinucci came up with the concept of this album when in hospital, Carter reached for the instrument after a heavy bout of pneumonia.

In “Exu Odara”, the Brazilian uses the fingerstyle to play a traditional melody associated with the Afro-American candomblé religion; the highlighted bass sound is very perceptible. In “Olodé”, the guitar functions like the berimbau or atabaque, the percussion instruments used in capoeira. The music is backed, and enrichd, by a small choir. In “Marquito”, in turn, the guitar resembles the guembri played by Gnawa people (but also Joshua Abrams, among others), and in “Tambú e Candongueiro”, the kora, an instrument from Gambia and Mali made famous by Sourakata Koité. The Brazilian aptly switches between the various styles, demonstrating sophisticated possibilities offered by simplicity. He occasionally sings too, and invites guests – on the record, we may hear Ava Rocha’s whispered, drawn out phrases, which function as an additional instrument here, Rodrigo Oga’s contemporary rap or the oneiric vocals of Metá Metá’s Juçara Marçal.

The record is filled with pop cultural Afro-Brazilian contexts. “Marquito” takes its inspiration from Kleber Mendonça’s brutal western “Bacarau”, and “Febre do Rato” stands for ‘uncontrollable situation’ in Pernambuco slang. Dinucci captures this very moment with his music, asking: where are we actually? There are plenty of such intertextual connections here, not merely serving as an addition to the music layer, but also painting a broader context for the record, again correcting that first impression that we’re looking at a pretty picture and listening to soothing music. Rastilho gradually draws listeners into a state of pensiveness. It is a personal comment on the contemporary world, the simplest possible gesture: reaching for an instrument, playing, looking towards the samba tradition, and creating a narrative about Brazil under Bolsonaro’s rule. In Brazilian, rastilho stands for fuse, but also fingerboard – an element of the guitar. In the record’s finale – an apocalyptic samba – the choir sings vamos explodir. The guitar is a good tool to do that. It hits hard, but quiets down at the end – so perhaps everything else will also come to pass? Rastilho sounds very universal, and this last track gives some hope for a not-too-terrible future in the difficult times we’ve found ourselves in.

Kiko Dinucci, Rastilho