– I spent most of my life outside of Iran. This was never my choice, so I felt a sense of void or longing for my homeland. In my mid-twenties, I started listening to more and more traditional Iranian music, until I felt like it was time for me to come up with some sort of Iranian music in that electronic synthesis framework – says Iranian composer SOTE.

Translation: Aleksandra Szkudłapska

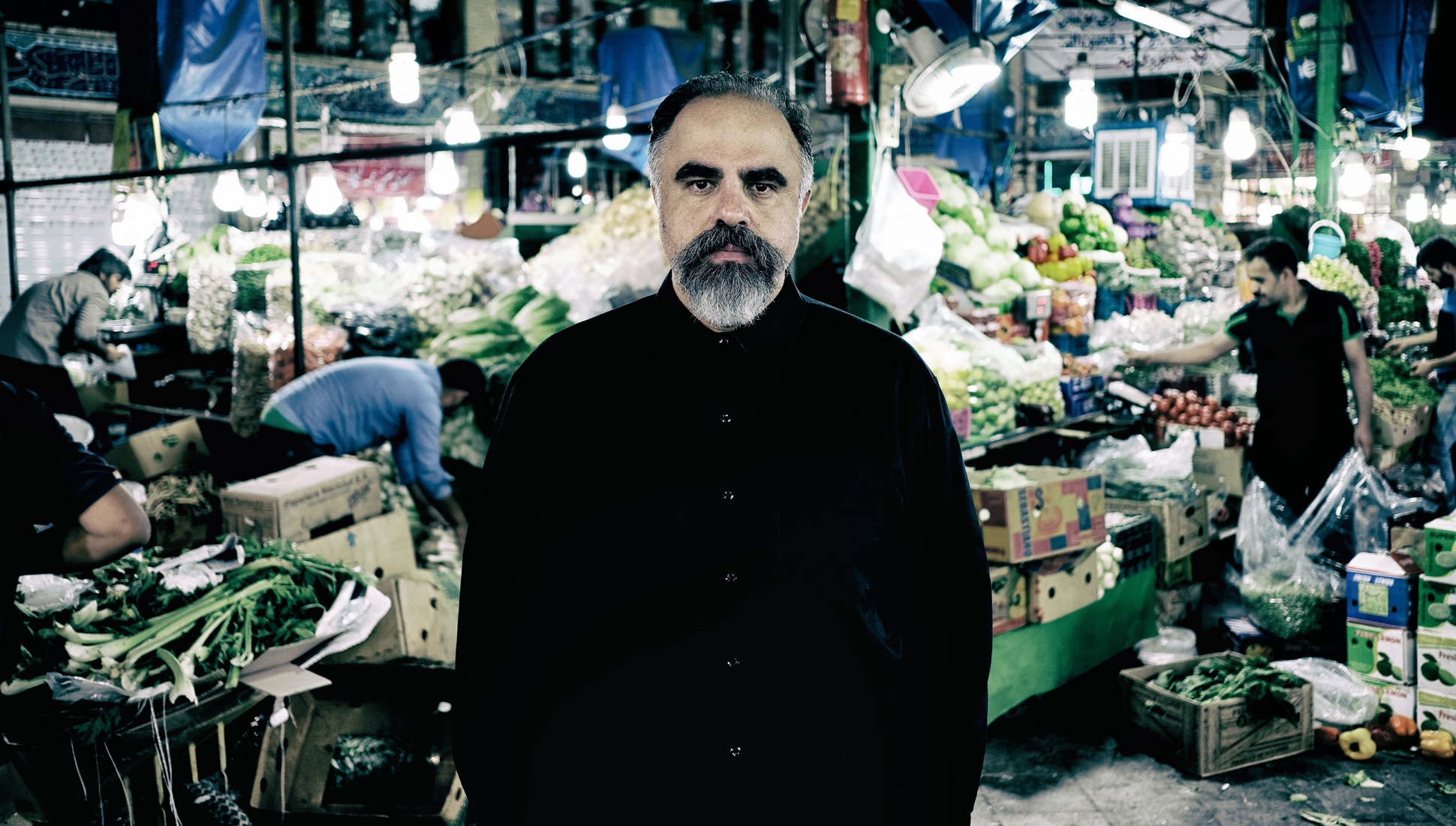

Ata Ebtekar has been active on the music scene for more than two decades now, although his beginnings are rather distant to what he’s shown to the world on his last two albums. This composer, rooted in the electronic scene and fascinated with sound, employs various means to synthesise electronic sounds with traditional Iranian influences. He first stepped on this path with his 2006 album Dastgaah, and continued this direction with the amazing Persian Electronic Music: Yesterday and Today 1966 – 2006. However, it was Sacred Horror in Design, released two years ago, which brought him the greatest recognition. Recording under the moniker Sote, Ebtekar skilfully blends the language of contemporary electronics and sound modulation techniques with Iranian scales, sonic ornamentation and traditional instruments. Each new record is surprising and reveals his new interests – the same goes for Parallel Persia released by Diagonal Records this year:

A tour de force that brilliantly combines the sound of traditional acoustic instruments and electronics into an impressive sound synthesis, offering an innovative glimpse at what futuristic folk can sound like.

Read my review here

It’s a fascinating combination of tradition and contemporary sound, Iranian scales and sophisticated production methods – while showcasing the lightness and erudition of its author. Sote’s work represents a prominent point on the map of electronic music, making a strong mark for Iran and encouraging listeners to take a deeper interest in its music scene. Apart from being a composer and teacher, Ebtekar has also founded the Zabte Sote label which showcases the most interesting contemporary electronic musicians from the country. This is a unique presentation of the Iranian scene, which – thanks to Sote’s label – has an opportunity to become recognized globally. I talk to Sote about tradition, his fascination with electronic music, Parallel Persia and the beginnings of his music career. On 6 October, Ata Ebtekar’s concert at the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Krakow will open the 17th edition of Unsound festival. Don’t miss it.

Jakub Knera: What was first: your interest in music or in Iranian tradition?

Ata Ebtekar: Definitely during my childhood, a long time ago, I was always interested in sound – not even lyrics or songs, but I was attracted to interesting electronic sounds. When I was really young, irrespective of the context of Western pop music, I was attracted to all these sound effects and the synthesis part of the songs. In my teenage years, I was purely attracted to electronic music.

Why was electronic music in particular so interesting for you?

I truly believe it is in my genes. I got into electronic music, because as far as sound production and sound synthesis is concerned, it’s limitless. Even today, with all the available tools and technology, you can still come up with very unique, interesting and unheard sounds. That’s what I find exciting, and it was the same when I was a lot younger, in my teenage years. To me, that was the big attraction: the fact you could make your own sound from scratch or a sound that hasn’t existed before. That mentality was and still is very attractive to me.

When listening to your new record, Parallel Persia, people who are used to the ‘electronic music’ term can actually be a bit surprised, because this could be seen as some kind of other sound. Is that what you look for in music? Other sounds?

Exactly, with most of my projects, my main goal is to put concepts to the side. Sometimes the concepts are set, sometimes there are no concepts – with or without them, the first thing is always trying to aim for what I haven’t heard before, something I haven’t listened to yet. It could be in my head: I feel I need to listen to something, but I cannot buy or download it, so I start making it myself.

Each project is a little different, but it’s always the same case: I want to make something that I want to listen to, but I can’t get it anywhere else. So I try to make it and then I usually call that– if, for me, it hasn’t existed before – the other sound.

You were born in Germany, then you moved to Iran, returned to Germany and later went to the United States. You lived in different locations – what memories do you have concerning listening to music in these different places? Listening to records too, but what I’m after is the experience of listening to electronic music in the communities, bars or clubs.

I lived in Iran until the age of eleven, and my listening experience was through all the cousins who made mixtapes for me and gave me cassette tapes of Western pop music and things like that. It was early 80s pop music and we all know there’s a lot of synthesizer elements in those tracks – I was really into it and although I didn’t know what I was listening to or what’s really happening technically, I was very attracted to those interesting sounds.

When I moved to Germany in my teenage years, I started really exploring – I could actually go out and pick my own taste. In high school, I formed a synthesizer band with my two friends – then I knew what was going on. I was very lucky that in Germany at the time you could actually go to clubs when you were fourteen or sixteen years old. In a small city where I lived, there were a couple of clubs for younger people that were open till midnight and after midnight we would leave, because then everybody around 18 would come in. We were lucky to experience the whole club culture at very young age. That was a very important experience for me in terms of listening to electronic body music: Front 242, Nitzer Ebb, some really rare and instrumental Depeche Mode stuff… That was my taste, experience and what I was attracted to.

Do you remember what made you want to make your own music?

As I said it was basically with my two best friends, who were Iranian too. Those were my only Iranian friends in Germany – I was very close to them, which is interesting, because most of my friends were German. We were all very much into the same kind of music and we were all interested in the sound aspect of music. One was more of a rhythm guy, the second one was more into melodic and harmonic stuff, and I was about the idea of sound. We all loved electronic body music and electronic pop music. It was a very natural process – we liked that kind of music and then, in our high school, we were allowed to stay in one of the rooms where there were some instruments and we could practice there. We basically started taking what was there, later we bought a couple of keyboards, synthesizers, we started to make our own drum kit with objects, trash cans and things like that. We also used tape players as samplers. We just started playing around and practising – our first gig took place at a high school event. Basically, it was very organic and natural.

When did you start making music on your own? Your first records released in the early 2000s on Warp Records or Dielectric Records, like Xoxo or Electric Deaf, were a bit different to what you are doing now.

It was when I moved to the United States at the age of seventeen. I was all alone, so I started making music on my own.

I remember my first synthesizer, the Roland JD-800, which was the first digital synthesizer that had analogue style knobs and features. Before that, most digital synthesizers had a little display menu and you had to go to menu under menu under menu to program your sounds. So, when JD-800 came out, I went to the guitar centre in the city because they had all kinds of instruments and bought it. I started playing around with it, I loved it – I started making music.

I had a Mac computer with a program called Vision, later renamed Studio Vision. I started making my own music by myself.

When did you connect the dots between electronic music you’ve been making and traditional Persian music? In 2006, you released Dastgaah and a year later Persian Electronic Music: Yesterday and Today 1966-2006 with the compositions of Alireza Mashayekhi.

That was later on, when I was living in San Francisco in my mid-twenties. I started feeling this emptiness and longing for Iranian culture. For the best part of my life, I was raised outside Iran, until I moved back to Tehran seven years ago. It was never my choice not to live in Iran – it was always because of circumstances like war that happened there. Because of that we moved to Germany. I had some of the best years there, but later my family decided to move to the United States. We tried to consolidate the locations of our family – I had a brother in the US, in Canada, a sister in Iran and my mother always moved around to be with all of us. The plan was to move to northern California. But anyway, I was raised basically in a very Iranian, Persian way in terms of culture – I love that, I always spoke Farsi at home, I love the culture and food. But because it was never my choice to not live in Iran, I felt this kind of void, emptiness. In my mid-twenties, I started listening to more and more traditional Iranian music. I became more involved in it and did more research on that type of music. It felt natural and organic to me. I had been making electronic music all my life – that’s what my passion is – but I felt like it was time for me to come up with some sort of Iranian music in that electronic synthesis framework. That’s how I made Dastgaah – it was a very natural progression. I wanted to make something very Iranian, yet it wouldn’t be my thing to start playing an Iranian instrument. I wanted to do it in very electronic way. Persian Electronic Music: Yesterday and Today 1966-2006 was a natural continuation.

With these two records, you tried to deconstruct Iranian music. With the next one – Sacred Horror in Design – the idea was to stay faithful to the tradition. What are the differences for you between these two perspectives?

In my early experience, I wanted to have that Iranian feel, that Iranian sound and colours, but I wanted to really break the rules of the tradition and deconstruct it. I had the mentality of “why can’t this or what I do be called traditional Iranian music” – which seems ridiculous now, but I did have it in my head at the time (laughs). It was a kind of rebellion towards traditional purists. I’m a bit of an anti-purist actually, to be honest (laughs). That’s what I did: try to deconstruct it and take stuff apart, yet I wanted the sound would be very Iranian.

Another very important thing at the time – which was very early on – was that I wanted to keep it beat-less. Electronic music back then was shifting towards all these beat-oriented genres. Back in the day, even before Dastgaah was released, I was thinking about why we had to always depend on beats. I love beats, that was my roots, techno, sure, but at that early stage it was one of my missions not to rely on beat-oriented electronic music – and the result were these two records.

Later on, I did another project: Ata Ebtekar & The Iranian Orchestra for New Music Performing Works of Alireza Mashayekhi, which was again an electroacoustic project where I took the compositions of Alireza Mashayekhi, a contemporary classical Iranian composer. I basically made another Iran-influenced project where I deconstructed his orchestra consisting of Western and Iranian instruments with noise and electronics. I left some compositions very close to original source material and some of them were completely deconstructed into new electroacoustic pieces.

And Sacred Horror in Design was completely different.

With that one I didn’t want to repeat what I did before. The challenge here involved keeping these two elements – electronic and Iranian tradition – without compromising any of them. That was a challenge: to keep the Iranian motifs and scale system, have them in harmony as sit together with very cutting-edge electronic sounds and production. No part should overpower the other one, both of them should have the same force.

You said you don’t want to repeat yourself and I think you’re really sticking to that. This year you’ve released Parallel Persia and it truly shows. While you’re using electronic and traditional Iranian influences, it seems to be this other, very futuristic sound. What was the idea behind this project?

In simple terms, the main difference between this and my previous albums is that with Parallel Persia, I reached deep down into my whole catalogue, to all the different kinds of electronic music I have done until now. With that in mind, I have tried to – again – include the Iranian elements in the picture. Although some parts are processed, most are left untouched, they are not deconstructed. If you have them sit together in harmony with the electronic parts, even now a listener can have a hard time telling apart what’s electronic and what’s acoustic. Parallel Persia is the most complex and layered record I’ve done. The dynamics is a lot wider – there are all kinds of moods, rhythmic elements, slow pieces, even vocals. It’s a much more mature piece of music.

At the same time, this electronic side is not heavy, it’s very folk-like, subtle and soft.

From beginning to end, there’s more variety for the listener as a whole. I agree with you. It’s not necessarily a heavy experience, even musically it’s richer.

Talking about Iranian instruments, you like to use real instruments, also during live shows. Electronic music often relies on samples. Why is this so important?

For this project I’m not necessary against music samples – with the available technology you can do a lot of interesting sounds with this tool. Maybe for next project I would prefer it to be that way.

Live instruments are a huge part of Iranian music in general – Iranian music is mostly about performance. For a very long time, it was not common for Iranian musicians to even write down their music on a piece of paper – it was always passed down from the master to the student, ever since the old days. The musician, performer, the performance, how a piece is performed, etc. has always played a very important part in classical Iranian music.

Everything I do, the very detailed, small variations of music that mix up Iranian music, scale system and motifs – it’s about the musician. For Sacred Horror in Design and Parallel Persia, it was very important for me to have musicians involved from the very beginning until the final performance. It was a challenge – it was very hard. Arash [Bolori] and Pouya [Damadi, with whom Sote recorded Parallel Persia – ed.] play in these crazy electronic parts that I composed with polyrhythmic elements, crazy rhythms and time signatures. It was very challenging for them to perform on top of it and be able to find their way around the music. But – and I think that what’s makes this project very special – there’s actually a very important human factor as far as performance is concerned.

You prepared the music first and then had them play on top of it?

It was different in different compositions. I usually don’t do many collaborations – it has to be someone who is a true friend of mine or almost like family. Then we have this level of comfort where we can trust each other. It’s not important for me to collaborate with the most amazing geniuses or famous people out there. I have different commissions like that, but that’s not necessarily attractive for me – I need to be very comfortable with people. I know Arash very well – he was also part of Sacred Horror in Design, and is an old family friend, he’s basically like a little brother to me. Pouya grew up with Arash, so I was very lucky to have these amazing musicians in my extended family circle. It got to a point where a lot of the pieces were pre-composed, then we were in the room together and I told them about my ideas or directions – sometimes directly and sometimes just a general idea to which they could improvise. Some pieces start with pure improvisation on the part of Arash, sometimes I compose around that.

Do you think that nowadays this kind of traditional, and very often rare element of non-Western cultures is making this kind of music more attractive compared to mainstream electronic or rock music?

It’s a cliché to say but the world is getting smaller because of the Internet. Everybody is getting exposed to different cultures. I’m glad that with Sacred Horror In Design and Parallel Persia, I have the opportunity to present Iranian influenced music to the international experimental music community. I think it’s an opportunity to change your perspective. Or perhaps even to inspire artists to go in different directions and adopt a broader outlook than that to which they‘ve been used to all their lives.

Parallel Persia is out now on Diagonal Records – you can listen and buy it here. On 6th of October will open Unsound Festival in Cracow.