– After the 1980 military coup – a very important and sad moment for Turkey – everything changed in a very bad way. After the coup, it was very uncool to accept basically everything associated with our culture. What was very cool was acting like a Westerner. So, I’m very happy that this is fading out and people are realizing that culture is not something like that – you can like it or hate it, but you cannot deny it. You can’t say it doesn’t exist – says vocalist and composer Gaye Su Akyol.

Translation: Aleksandra Szkudłapska

If, like me, you’re an avid follower of alternative music, you’ve clearly noticed the growing number of young Turkish artists whose music is informed by the Turkish folk and psych legacy. The last months have seen a crop of intriguing records by young generation musicians such as Derya Yıldırım & Grup Şimşek, Adamlar, Umut Adan, Gözen Atili who goes by the moniker Anadol of the Dutch people from Altın Gün who record Turkish hits. There is one name, though, that really stands out against this background: Gaye Su Akyol, who in autumn 2018 released her third LP, İstikrarlı Hayal Hakikattir, on the amazing Glitterbeat label.

Gaye regularly underlines her connection to 1960s and 1970s psychedelic Turkish rock and artists such as Barış Manço, Erkin Koray and Selda Bağcan. She often performs their songs live, and her cover of a Barış Manço piece is one of the tracks on her latest album. Akyol combines fascinations with Anatolian melodies, rock’n’roll psychedelia and synthesiser swagger, which imparts a cosmic character to her music. This is clear in the title, opening track of her latest album, which also brilliantly conveys the accompanying motto: consistent fantasy is reality. In interviews, Gaye frequently talks about creating a parallel musical world, able to combat whatever is currently happening in our world – I also managed to talk to her about that.

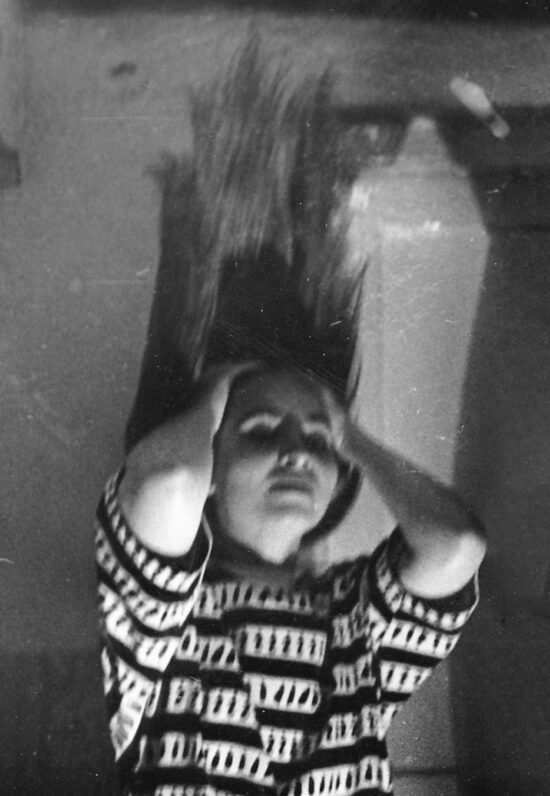

The interview was to take place before the Globaltica festival, but because of an intense concert day in Istanbul we were not able to talk, and a journalist from The Guardian beat me to it. Luckily, postponed is not abandoned, and thanks to the organizers of the Gdynia event, I had the opportunity to meet the artist when she visited the Polish seaside. And later saw her fascinating concert. Gaye and her band are not just very thoughtful and consistent in terms of the music they create – they also take care about accessories and creating a cosmic ambience on stage. The singer wore a black costume and shiny silver cape, while her band were dressed in long black robes and Zorro-style masks. Music-wise, the rock formula is brilliantly enriched with Turkish rock and psych influences. Gaye casts a glance at the past, but at the same time has a powerful and consistent vision of the future, which really came through during her show. Above all, though, she is a very conscious artist – both in terms of image and the topics she wants to talk about from the stage. Her music is not just a colourful narrative; it is a dialogue with reality, an attempt at reining it in through original form and metaphor, strongly rooted in the here and now. The glitter of rock’n’roll meets a powerful message here – clearly visible and heard at Globaltica, when a crowd of Turkish fans was really losing it in the front rows. The Polish part of the crowd too, myself included, of course. Below is a summary of our conversation that took place a few hours before that gig.

Jakub Knera: Do you remember when you first started enjoying and then playing music?

Gaye Su Akyol: One of my first memories is that of my father bringing home a keyboard, which I started to play. This was the first moment when I really enjoyed playing music a lot. Another thing is that my mother was an amazing singer and she was always singing old Turkish songs at home. So as a child, I was raised hearing her beautiful voice and trying to mimic her, remembering these old songs. It’s very hard for a child to learn them, but when I was five, I already knew lots of old Turkish songs. These are my first memories. Then I started thinking that I was going to make music and paint – this is what I started telling to friends of the family asking me what I wanted to do when I grew up.

The music you make is strongly rooted in the Turkish tradition. Nowadays, a lot of artists reach for traditional influences when making music. How important was traditional Turkish music in your family, neighbourhood or for your friends?

There are different genres of traditional Turkish music – there is Turkish folk music, there is classical Turkish music, also called Turkish art music (from the word sanat, meaning ‘art’). It comes from Ottoman style music – in the old period, it was a specific genre for sultans. These are the roots of this music. I was raised listening to these kinds of genres because of my mother and father. In Turkey, arabesk music was kind of a taboo [while the Turkish mainstream and urban elites largely shaped their cultural tastes and identity based on Western culture, arabesk combines Anatolian, Arabic and Kurdish influences; since the 1950s and 70s its main followers were migrants from the rural areas of Turkey, which were often left out of the 20th-century Westernization process – note by JK]. The government didn’t let people listen to or sing it for a long time, we’re talking about the period after Atatürk’s republic here. It wasn’t forbidden as such, but there was a belief that arabesk music was making Turkish culture and music kitschy. It was a taboo, but when I was a child people were listening to arabesk in their homes, just without letting others know because it also wasn’t cool. More than being a forbidden thing, it was just not cool enough to share that you were listening to arabesk. In my music, this is also another ironic part – I use it with different kinds of symbols, metaphors. In a way, I see it as cultural heritage.

You cannot deny something just because it’s forbidden: people were listening to it, people were into it, I was always hearing this kind of music in my childhood. So, to come back to your question, music has always been very important for Turkish culture – there are a lot of genres, also dance music or Turkish wedding music. I really love to put these different genres in my music.

Is this traditional music still popular in Turkey?

I think people are not very eager or open about listening to old school Turkish music. There are bands like us and other bands that feel this is a kind of heritage, see the beauty of our own culture, and start to respect this music. I’m very happy about this situation because after the 1980 military coup – a very important and sad moment for Turkey – everything changed in a very bad way. After the coup, it was very uncool to accept basically everything associated with our culture. What was very cool was acting like a Westerner. So, I’m very happy that this is fading out and people are realizing that culture is not something like that – you can like it or hate it, but you cannot deny it. You can’t say it doesn’t exist. This is what I do: I accept what exists, and the emotions are up to you.

There are more and more bands playing Turkish music, sometimes from a very interesting perspective – like Altın Gün, who are not from Turkey, but are playing Turkish music.

Covering actually.

I was wondering about the sources of this boom or renewed interest in Turkish music among young people, who often do it in a modern way. That’s what you do too – you’re not recreating old music or playing covers.

It’s not very popular still – there are some up-and-coming bands, you could maybe count six or seven bands in that genre. There are also sub-genres that one could add to the psychedelic Turkish rock music scene. But I think there’s going to be much more of that because it’s hugely hyped right now. Hypes come and go, they are not eternal. And covering old Turkish songs doesn’t sound very artistic or authentic for that matter, but what Altın Gün are doing is really good – because what they use, what they play and what they recover is very truthful. But I really need to hear some new songs – that’s what we deserve. I’m listening to many different kinds of music and when I started playing my own thing, this music just came up. It’s not something I planned or made formulas for – music should come from instinct and your own perspective. This is what I’m doing.

The psychedelic Turkish rock is a very interesting genre for the world because it seems to be a lot of genres coming together to make something new. It was very fresh in the 60s and 70s and it’s still new for the world. It’s the symbol of liberty and fighting against fascism – that’s why I find it very precious. The coup made this psychedelic Turkish rock disappear, but now, 20-30 years later, it’s coming up again.

I don’t believe in hypes and fashion, but I hope there will be some other bands who are going to make music based on their instincts.

You mentioned rock’n’roll and the aspect of music used as a vehicle to rebel against something. Is this something that is important for you? Should music respond to things that are happening around us?

Actually, slogans don’t work. They don’t change things. Real music can make a change. What I’m trying to do is write down my feelings, riot visions and rock’n’roll perspective, enriched with a new kind of symbolism. I’m making a metaphorical world and I want people to enter this new world with different tastes, different cultures and tendencies. This music contains riot, rock’n’roll and accepting its own culture. It’s important at this point too. If I’m listening to a Japanese band, I need to hear their own cultural roots. They don’t have to play their folk music of course, but what they hear, listen and get from their own culture is what I’m really interested in. If they are another Western based rock’n’rollers, it’s just looks cheesy. Maybe they think it’s cool, but they are just another copy-cat of a culture. Children of capitalism. We should also think about these issues.

The Colombian Eblis Alvarez of Meridian Brothers and Chupame el Dedo once told me that for him it’s interesting to make local things global instead of making global things local.

Exactly! That’s what I’m thinking! Think local, act global.

But let’s devote a moment to global music now: you said that one of your inspiration was Nirvana. Were there any other points in your life that got you into playing music?

Nirvana was a gamechanger in my life. I was maybe ten years old, definitely not more than eleven. My brother was a grunge fan and we were in my grandmother’s house – and I was getting very bored. My brother went to my mother’s car. He was listening to something and I just chased him, sat down inside and started listening to his music. I asked him what it was, and he said “Nirvana, they’re a really good band”. He was listening to Smells Like Teen Spirit and I remember feeling like “This is what I was looking for, this is exactly what I want to hear”. I was inspired, shocked and mesmerized at the same time. After that moment, I became a grunge fan too. I discovered Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Blind Melon and lots of other bands, and then moved on to Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, Metallica, etc. It’s like the boxes opened and the rest of them came pouring out. I had just entered the rock’n’roll building.

It’s interesting how these two perspectives – the Turkish elements and rock’n’roll – meet somewhere in the middle. Another thing I’d like to find out more about is your use of metaphors, for instance in terms of your last album cover, the science-fiction aesthetics of the video or the title İstikrarlı Hayal Hakikattir. Can you tell me more about the idea?

The title means “consistent fantasy is reality”. What I mean by this idea is that we need a kind of counter-reality to fight against evil. The world right now is turning with the evil powers – they are ruling the world, because they believe in what they think and they are coming together. There are more eager or more professional to come together than us. We don’t believe in anything, in coming together, in fighting against it, because we don’t believe we can win. So the whole idea is that I’m creating a counter-reality – a new reality out of consistent fantasies. It’s not meant to be some new age shit – I always say that this is not what I’m on about here. What I mean are real things – as explained by Einstein or quantum physics, the whole reality is different in the quantum mechanics version. We are living in one reality and they’re living in another one. We really can create our own reality and what we are living now is our personal reality. So what I say is this: if all these realities come together and make a new one, then we can fight against this evil.

Do you believe that art can influence people to start thinking about it?

It’s up to them. I’m just making good art. Art is talking here – if somebody understands a different thing, it’s their own illusion and I accept that too. I’m not a kind of teacher, trying to teach people a certain thing. Mine is a counter, artistic way of thinking. If you like it – you can join this kind of perspective or have your own too. This is just my own artistical way of trying.

But do you generally believe that art can communicate some political or social aspects?

Sure. I’m the living proof of it. What I am is the evidence of what I listen to, of my tastes. I’m a constant version of what I’ve already experienced. So if I give this new experience to the people, this might end up changing their lives. I believe art can change anything.

On your last album, you included a cover of a Barış Manço song. What made you choose his composition? What other Turkish artists are important for you?

There are a lot of very inspirational musicians from the psychedelic Turkish scene of the 1960s and 70s. Barış Manço is one of them. Erkin Koray, Selda Bağcan, Moğollar – these guys are the inventors of this music. I picked up this song, Hemşerim Memleket Nire, because the lyrics are very beautiful and very precious to me. It says: hey mate, where are you from? And the answer is: this world is my hometown. The idea behind this song is very precious – where you’re from is not as important as what you are doing in this world. What’s your purpose? What are you fighting for? What’s the goal you want to reach? It’s not about where you’re from, but where you’re going to.

There are lots of other amazing people I mentioned. I sing a lot of their songs on stage, Selda Bağcan or Erkin Koray. You should look for translations of their songs – generally speaking, they talk about liberty and fight against fascism, against the bad things done to the poor by the rich. The economic mindset is very important in these songs.

Do you want to remind people about these songs or show how topical they can be now?

I think both these things.

Composing a song again or covering it is almost like making it again. If you do it exactly the same as it was before, it doesn’t sound cool or make any sense. Usually, the original version sounds better. If you don’t put anything new in it, it is usually released for economic reasons only. If we decide to do that, I prefer to make it in an original and authentic way, to show people that these songs can also be like that. This is what I’m looking for in covers.

When Nirvana covered a Shocking Blue song, it was a completely new song. I heard it from Nirvana for the first time. “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?” was also a cover and I also heard it for the first time from them – it was very shocking. And the original version was mind-blowing. These were two different songs. That’s what I prefer: to make something new out of it.

Yeah, the whole point of making covers is not just playing the same song again, but remaking it in a new way.

And sometimes it’s even harder than making a new song – because you should obey the rules, but you should also break the rules. It’s a very artistic way of thinking. If someone makes a good cover, you should respect them. I do! (laughs).

İstikrarlı Hayal Hakikattir was released by Glitterbeat. You can listen the album on artist’s Bandcamp profile and buy on the label’s website.