Amirtha Kidambi’s idiosyncratic vision of improvised music has found a brilliant outlet, informed by new sounds, yet still maintaining its distinctive character. From Untruth ranks among the most interesting, intriguing and poignant musical visions of recent years.

Translation: Aleksandra Szkudłapska

While Holy Science, composed solo and then rearranged for a quartet, was still strongly rooted in Carnatic music, with the lengthy drone-like, monotonous passages being its main feature, From Untruth represents a massive step forward. Three years after her debut album, Amirtha Kidambi, a young multi-instrumentalist from New York, returns as a frontwoman with her brand new work: a brilliant epic about the contemporary world created in the spirit of improvised music, but with a modern, occasionally even futuristic sound. She is backed here by three amazing musicians: Matt Nelson on soprano saxophone and Moog, Max Jaffe on drums and sensory percussion and Nick Dunston on double bass (this instrument was previously played by Brandon Lopez).

AMIRTHA KIDAMBI – INTERVIEW:

I basically felt that even on a personal level, for myself and my own sanity, on From Untruth I needed to express some things very directly. I love abstract and instrumental music and improvising without lyrics, but there’s something about the moment and what is happening that made me want to put out some kind of a reaction.

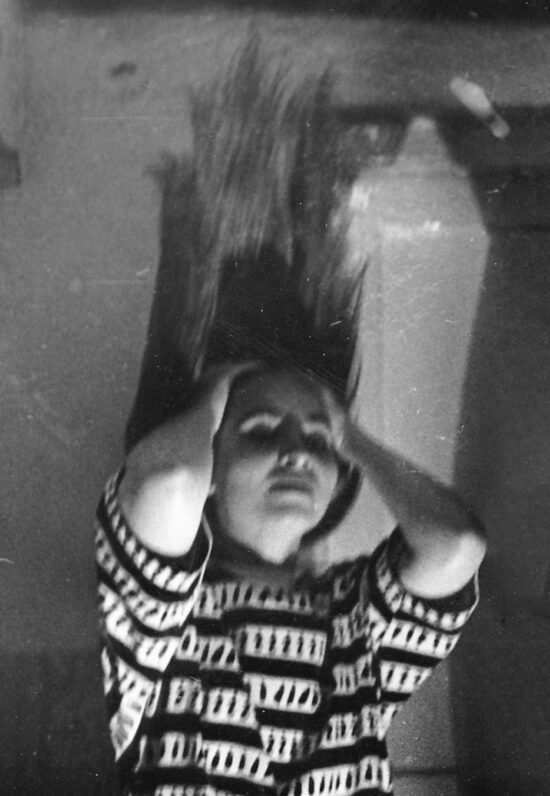

Kidambi herself is vital too: apart from singing, she plays the harmonium and synthesizer. The young artist is involved in a number of projects – from the amazing Code Girl with Mary Halvorson, whose album was released a year ago, through Seaven Teares with Charlie Looker (of the sorely missed Extra Life), her collaboration with Lea Bertucci (a record is in the works), to Robert Ashley’s opera and the Lines of Light vocal quartet. The Elder Ones is her brainchild, though: as opulent as it is poignant with its refreshing approach to improvisation. Kidambi really builds on her vocal potential here (which on could already hear in Code Girl). She sometimes resembles a prophetess, reciting contemporary hymns like the opening to “Decolonize the Mind”, where her voice is supplemented by sonoristic hisses and creaks. She can shout with punk, throaty verve, like in the ending of “Eat the Rich”, where she also employs the konnakol technique. While her lyrics are evocative and topically involved, her voice often functions like yet another instrument. Still, the clearly enunciated, strong slogans (eat the rich / or die starving in the opening piece) or the closing repetition, slightly resembling a lullaby (of birth and rebirth) are instantly etched on the memory.

Yet the key factor is how Kidambi works with other musicians to implement her vision – hers is a consistently coherent outfit, where everyone has clearly defined roles. The acoustic possibilities of improvisation (most often emphasized in the Dunston-Jaffe rhythm section) sound very raw, one can sometimes even hear the ‘wooden’ resonance of the instruments. Kidambi and others often reach for electronic instruments too, though – luckily, instead of sounding overwhelming, they act as an inventive development, accentuating a number of details or serving as a counterpoint to acoustic sounds.

The album is very dynamic: when the steady rhythm generated on the harmonium in “Eat the Rich” is contrasted by Nelson’s saxophone spasms, the piece gains momentum and instantly explodes. Directly afterwards comes one of the highlights of the entire record: the saxophonist climbs to the very highest registers, wailing on his instrument for a few pregnant, otherwise silent seconds, before being joined by the remaining musicians and a delicate accompaniment of the Moog.

“Dance of the Subaltern” is based on an electronic groove, which roughly halfway through the piece evolves into a duel between Moog and sensory percussion, only to swiftly shift to a controlled instrumental cacophony topped with acid synths (with melodiously chanted we will rise / we will drown somewhere in-between). In “Decolonize the Mind”, Kidambi’s voice basically enters operatic territory, accompanied by Dunston’s lengthy bow strokes. The singer sounds like a shaman, her voice becomes multiplied – a meaningful effect as she sings the ambiguous play on words (shut us up or shut us down / keep us out or keep us down), which – in the context of the piece and the entire record – can be read as a manifesto of people of colour in the U.S. The title piece seems the most tranquil and hopeful at the same time. It’s lyrical, a little folky; after Dunston’s beautiful solo opening and tumultuous middle part comes the long, vibrating synth as if taken out of Twin Peaks and Kidambi’s singing dies down to a lullaby.

Apart from a hefty dose of emotions, the album is also packed with a multitude of details one can explore for hours on end. They’re genuinely moving. Chilling even. Kidambi’s idiosyncratic vision of improvised music has found a brilliant outlet, informed by new sounds, yet still maintaining its distinctive character. She also did a brilliant job with casting her musicians, who add character and additional sound layers to the pieces. The result is a contemporary, colourful, timeless story, fuelled by words about violence, colonialism, capitalism and racism shouted with genuine punk anger. From Untruth definitely ranks among the most interesting, intriguing and poignant musical visions of recent years.

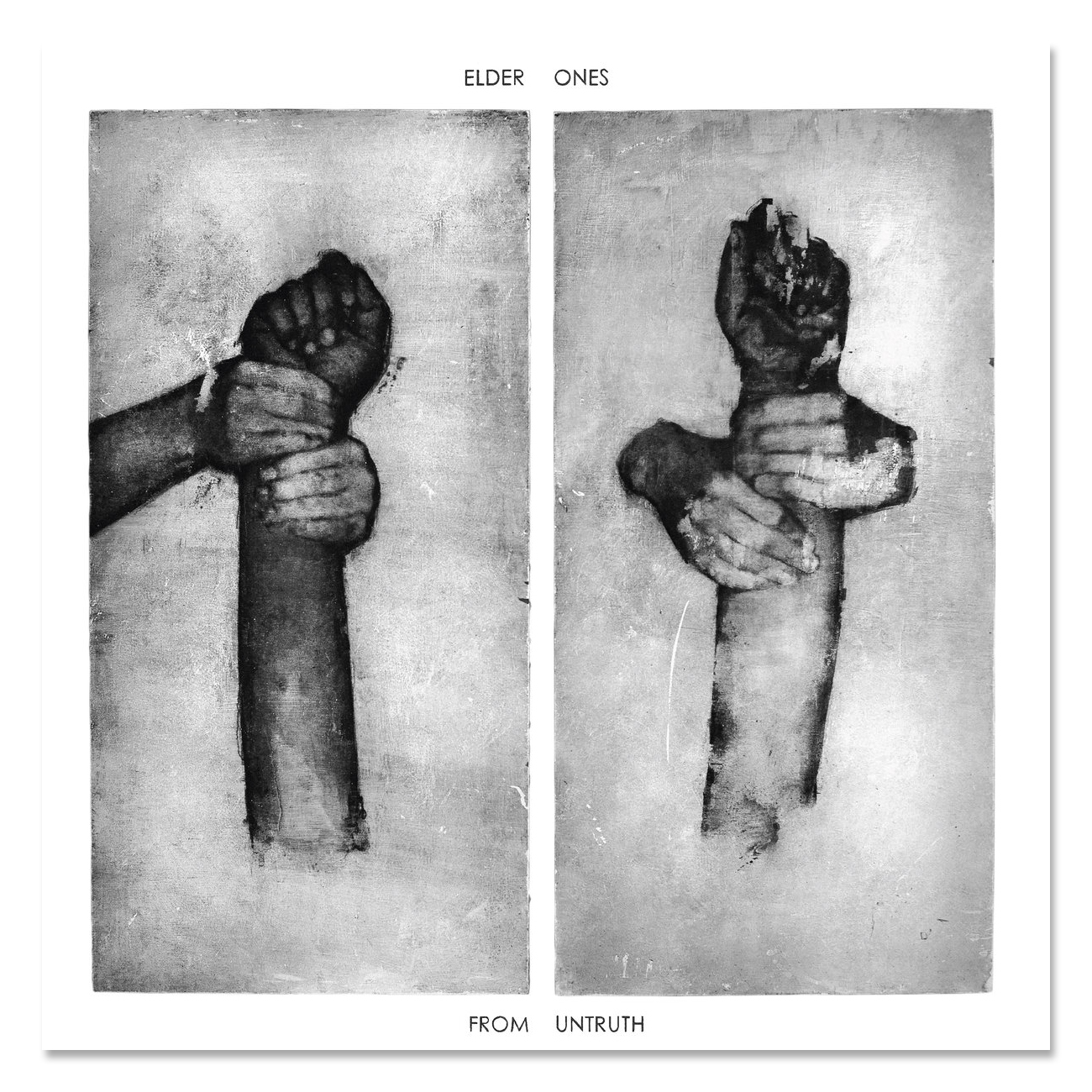

Amirtha Kidambi’s Elder Ones, From Untruth, Northern Spy

LISTEN: 🎶Spotify, 🎶Tidal, 🎶Deezer, 🎶Apple Music