Sho Madjozi sounds best in parts that draw on contemporary influences from her native Limpopo and gqom, like in the “Hutu” or “Kona”, with its fresh blend of shangaan electro. These tracks are distinctive and sassy, offering a lighter, wilder and definitely more pop-oriented take at gqom.

Translation: Aleksandra Szkudłapska

South Africa is an important reference point on the global map of electronic music. Since the 1990s, when kwaito – a style combining house and traditional African sounds – emerged in Johannesburg, its citizens have been referred to as the biggest consumers of house music. Yet new scenes and genres keep cropping up in the country, the most powerful and influential of which possibly being gqom – a raw variant of kwaito, stripped down to synthetic percussion parts (and represented by Rudeboyz, DJ Lag, Dominowe or The Sound of Durban compilation). According to Woza Taxi, it started out as a peculiar type of Muzak for taxis – and while I’m not 100% sure if that was really so, the documentary is definitely worth watching. The music, recorded in small studios (i.e. using Fruity Loops on laptops) and dubbed the answer to Chicago’s footwork, quickly found its way into the mainstream. One example of this phenomenon is Sho Madjozi, who played a mind-blowing gig at Krakow’s Unsound festival in October 2018, back when she only had two solid singles (“Hutu” and “DumiHi Phone”) under her belt.

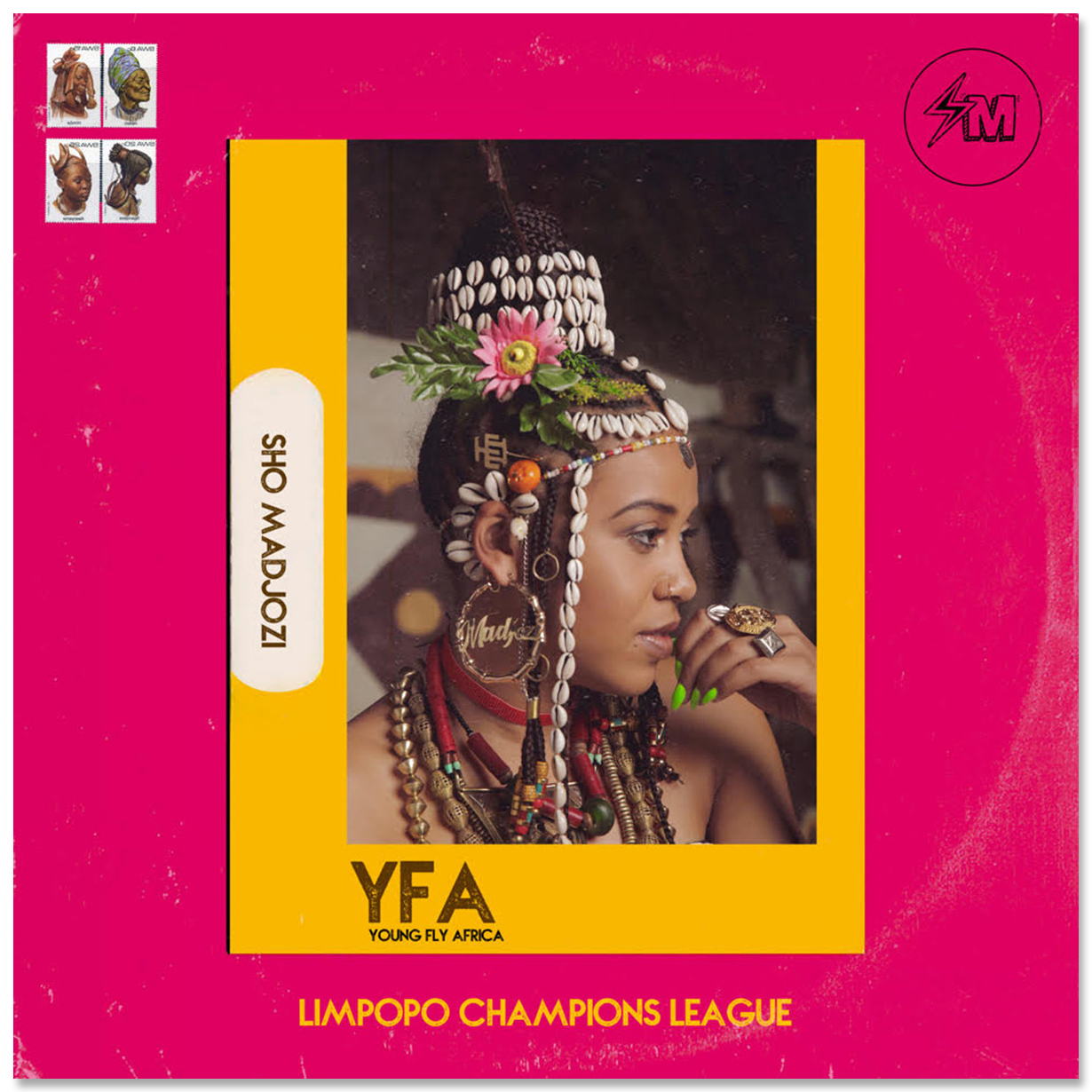

Her debut album, Limpopo Champions League, sounds best in parts that draw on contemporary influences from her native Limpopo – South Africa’s northernmost province – and gqom, like in the aforementioned “Hutu” or “Kona”, with its fresh blend of shangaan electro. Both inspirations appear in the opening number, the witty “Ro Rail”, while “Changanya” juxtaposes electronica with traditional instruments. These tracks are distinctive and sassy, offering a lighter, wilder and definitely more pop-oriented take at gqom. The fact that there are more than one shades to gqom became clear from the piece recorded by one of the producers of Sho’s album, Tboy Daflame: “uBaba kaDuduzane”, which incorporates clips of South Africa’s former president Jacob Zuma, and quickly went viral.

Madjozi (aka Maya Wegerif) presents herself as a pop star; her name, Sho, is shouted on the record time and again, together with the characteristic call “iyaah”. In the intro, she is showcased as an art and fashion phenomenon, after which she calls herself an ambassador – and while this hypothesis may be a little stretched, Sho Madjozi has definitely carved out a fully-fledged artistic persona for herself. She has not forgotten about her roots and musical background, referring to tsonga (that’s the language of her rap) and xibelani dance, the indigenous tradition of Limpopo, with its trademark colourful skirts. In colonial times, Swiss missionaries forbade women to wear them, as they were thought to symbolise paganism. Nowadays, the skirts are a sign of emancipation and empowerment; Madjozi tells their story in a documentary film she co-authored, and craftily incorporates them into her stage outfits.

While most of her lyrics celebrate youth and hedonism, certain post-colonial traits are also there, for instance when she addresses the white community in “Yaz’ Abelungu”: Being umlungu must be great / They don’t even have to learn your name / My boy, what’s the point? / All black people look the same. In Zulu, “umlungu” means a white person, but it’s hard to not consider this phrase in the context of “African music” – a term often used in a hurtful manner, as the music is as diverse as the continent itself. Even if Madjozi’s social involvement is served in a pop dressing, I’m still buying it. Things get worse, though, when the album becomes overly contrived in terms of production, starting to resemble US outfits such as Major Lazer. This is when it gets bland and banal, like the dreadful “Don’t Tell Me What To Do” or „Going Down”. Not just because the music sounds much more interesting when Sho sings and raps in Kiswahili or Tsonga, but because this makes her lose her musical personality in the pap of globalised pop. The dualism does not serve the album well, as genuinely brilliant tracks are counterbalanced by vapid pieces devoid of any edge or uniqueness. And while I understand the need to reconcile the alternative and the mainstream, the local and international audiences, this is when Limpopo Champions League takes a turn for the worse. Its strengths lie in authenticity and a twist on tradition – that’s what makes it sound modern and fresh, and for this part, the album is definitely worth a listen.

LISTEN: 🎵 Spotify 🎵 Tidal 🎵 Deezer 🎵 Apple Music

Sho Madjozi, Limpopo Champions League, Flourish and Multiply